Adapting to Change

Adapting to life in Beverly Hills challenged everything I thought I knew about people and places. Academics and social skills got tested. Unable to become invisible, I tried harder to earn recognition and respect.

I stood on uneven ground. I wanted acceptance by my peers and most of all to fit in. I wanted teachers to like me. I needed some measure of acceptance, especially since I felt insecure at home.

“We all have our best guides within us, if we will listen.”

The 119 eighth graders were sorted into four pods, and I was placed in 8-A, classified the “brightest and best students,” because I came with highest grades from my school in Las Vegas. Big mistake.

The most humiliating experience of adolescence occurred on the playground at school. A burly guy named Steve, who was in 8-C, started yelling the acronym, “FBR in the BLR,” gaining a chorus of voices as others joined his chant on our way back into the building right after P.E. I didn’t know until then that Steve had nicknamed me “Fat Bastard Reeves.” He had conspired along with the guys following him to throw me into the boy’s locker room, hoping to further humiliate me. Which they did.

On another day, classmates stood around to watch my showdown with Steve, who was built like a linebacker, a head taller than me. Engaged in a battle with words, when I said to Steve, “You couldn’t punch your way out of a brown paper bag,” the circle of bystanders collapsed around me, as if suddenly they could admit I might know things they didn’t. Not one person had ever heard such a saying.

Daydreaming Days

It took less than thirty minutes to walk to school, down Spalding Drive to Moreno, which curved in front of the high school, then a right on Lasky to Santa Monica Boulevard, where the same crossing guard greeted me each morning at the intersection of Wilshire Boulevard. That year, she gave me a birthday card picturing caricatures of four mop heads: “Have a Happy Birthday. Yeah, yeah, yeah!”

The meaning was unmistakeable as the Beatles had invaded Los Angeles earlier that year. I wonder why she did that? How could the crossing guard have guessed how much her smiling face helped me go far beyond crossing a street safely?

From that intersection, I walked straight down Wilshire to Whittier Drive, turned right and entered school, walking up the wide tiled steps through the imposing entrance to El Rodeo school, with its domed bell tower and Spanish architecture. Across Wilshire from the school, the Beverly Hilton Hotel still occupies that prime location.

El Rodeo School

"El Rodeo de Las Aguas" (The gathering of the waters) 1927

Before the end of the school year, our eighth grade class had orientation at Beverly Hills High School. I had walked past that school so many days on my way to El Rodeo. And every day, I imagined what it would be like to attend the four years of high school on that sprawling campus.

The high school gym had a swimming pool under the basketball court, sliding back into the wall and was used for a scene in the Jimmy Stewart movie It’s a Wonderful Life. Much later, that movie would mark a pivotal moment in my life.

My educational opportunities expanded with classes in both English and English Literature, Art, Music, Science, Home Economics, French, and Math. My math teacher Mrs. Gross was also my homeroom teacher and I grew to love her above all other teachers. She looked ancient because the wrinkles on her face hung like an Austrian shade. Gruff at first, she proved to be the kindest, most gentle soul I’d ever met. I needed the acceptance and approval of people I admired because I did not get these needs met at home.

Some of the other teachers appeared impressed with their own importance, bordering on snobbery. My mother said that the word “snob” means “without nobility.” It struck me as odd that so many people who worked in Beverly Hills acted superior, looking down on others.

I particularly disliked my English Literature teacher who although well past middle age, she always wore pink, like Dolores Umbridge in Harry Potter. Only Miss _____’s clothes were loose and flowing, as if she wanted to appear younger, her wings wafting over our heads, the faint scent of some crummy fragrance trailing. She preferred the boy students, and too much like Miss Umbridge, she made me feel as unwelcome as a Muggle at Hogwarts.

Stern and tough, there was no one like my science teacher Mrs. Bergman, who somehow left the deepest impression on me. No nonsense, her classes buzzed with activity and enthusiasm. I don’t remember a single thing she taught that year except that my science project “Photosynthesis of a Plant,” brought my grade for that quarter up to a B.

While living in Beverly Hills, I encountered a number of celebrities. Rarely however, did residents approach movie and television stars for their autograph. Typically, if you made eye contact, they would acknowledge you for recognizing them and then go on with their lives, relieved not to be accosted the way celebrities are today.

During our school spring concert, our choir director spotted Debbie Reynolds in the audience using the opportunity to connect and chat with people she knew. Debbie’s daughter, Carrie Fisher was in second grade at El Rodeo. Mrs. Haldeman was furious that a performer would distract from our choir’s performance. She also told us at the break Walt Disney was sitting in the balcony. I gasped.

Reality TV

My awkward year of living dangerously in Beverly Hills included one stellar achievement. Sitting at the lunch table hearing people around me talk about the party––The party––an invitation to Patty’s graduation party held at her parent’s beach house in Santa Monica suddenly mattered to me more than grades or clothes or any social validation. Patty was the Queen Bee attracting all the attention, honey to my childish heart. Being invited was not the same as belonging, still, I wanted this as much as I’d ever wanted anything.

How could I get her to invite me? Why would she want to? Why was this so important to me? How did it happen?

The night of Patti’s party captured a surreal scene of luxury living beyond the dream-making illusions of movie magic on larger-than-life screens. This was real life. Real people lived here. This was their life.

Was I wrong to want another life?

Along this stretch of Santa Monica, outside the back gate lay the Pacific Ocean, waves lapping the sand, the beach empty of public beachgoers. Ten of us, 14-year-old giggling girls, frolicked on the beach. Excited. Invited. Included. An insane privilege, I tried not to gawk at the Goldstein’s house. It even had a swimming pool and a tennis court! This two-story house on the beach was not the family’s full-time residence. Patti’s family lived in a mansion in Beverly Hills. Patti’s dad was a television producer. Patti was the girl any young girl would want to be.

Once seated at tables set with china, crystal, and sterling, maids appeared. Wearing black and white uniforms with starched caps like tiaras perched on their heads, they held trays of food to serve us dinner. Which fork do I use?

My mind flitted between scenes in fancy restaurants in Beverly Hills or Hollywood, or places on the Las Vegas Strip where some man who asked my mom out to dinner took me along. Calibrating, it was one thing to have dinner in a dim-lit restaurant, served a meal from a menu with prices that reflected extravagance, but inside someone’s home, the experience felt magical. This one night made me feel like Haley Mills, as if I had stepped into a Walt Disney movie.

More than the name on a map or a 90210 zip code, Beverly Hills forged a tributary in my adolescence, gave me experiences that fed my fantasies, inhabited my dreams, contributed to my longing to belong. Somewhere.

By the end of that school year, I had gained modest acceptance by my peers, if not outright approval.

I look back upon my vulnerable adolescent self with compassion.

What I needed was to be brave. What I wanted was to belong. I worked so hard to connect with these strangers, comprehending later, they had no reason to notice me, much less accept me. I wasn’t even Jewish.

This feeling of almost belonging made it harder to leave the few good friends I had made and move to another town. Another house. Another school. As soon as I graduated from the 8th grade, we’d pack and be gone.

So many other memories have washed away, but keepsakes remain like prized sea shells . . . the yearbook signed by classmates and teachers. Our class sponsor danced with me during the El Rodeo graduation party at the Los Angeles Country Club. He was father of one of my classmates–class vice-president. Movie star handsome, elegant, his neighbors were Jack Benny and Lucille Ball. While dancing, he told me the high school graduating seniors were celebrating on his private yacht––on their way to Catalina Island. Picture that!

Not only did I dream of attending high school in Beverly Hills, after graduating from BHHS, I hoped to go on to U.C.L.A.

I look back on that one school year as formative of both my social and intellectual education. I did not retreat when I could have made myself small and invisible. I entered that scary arena. Resisting the shame I felt for not being like the others, I worked to engage and learn as much as I could

Awakened and Aware

What was impossible for me to know then was how God would use this experience to contribute insight throughout my life. Curious about the extra school holidays for Jews, I wondered what these days off represented. No one ever invited me to worship with them, nor did I, the only Gentile in the entire class, have an inkling about the weekly Sabbath. Yet I wanted to know what made Jews distinctive?

I sensed that the Jews knew things about God that I did not.

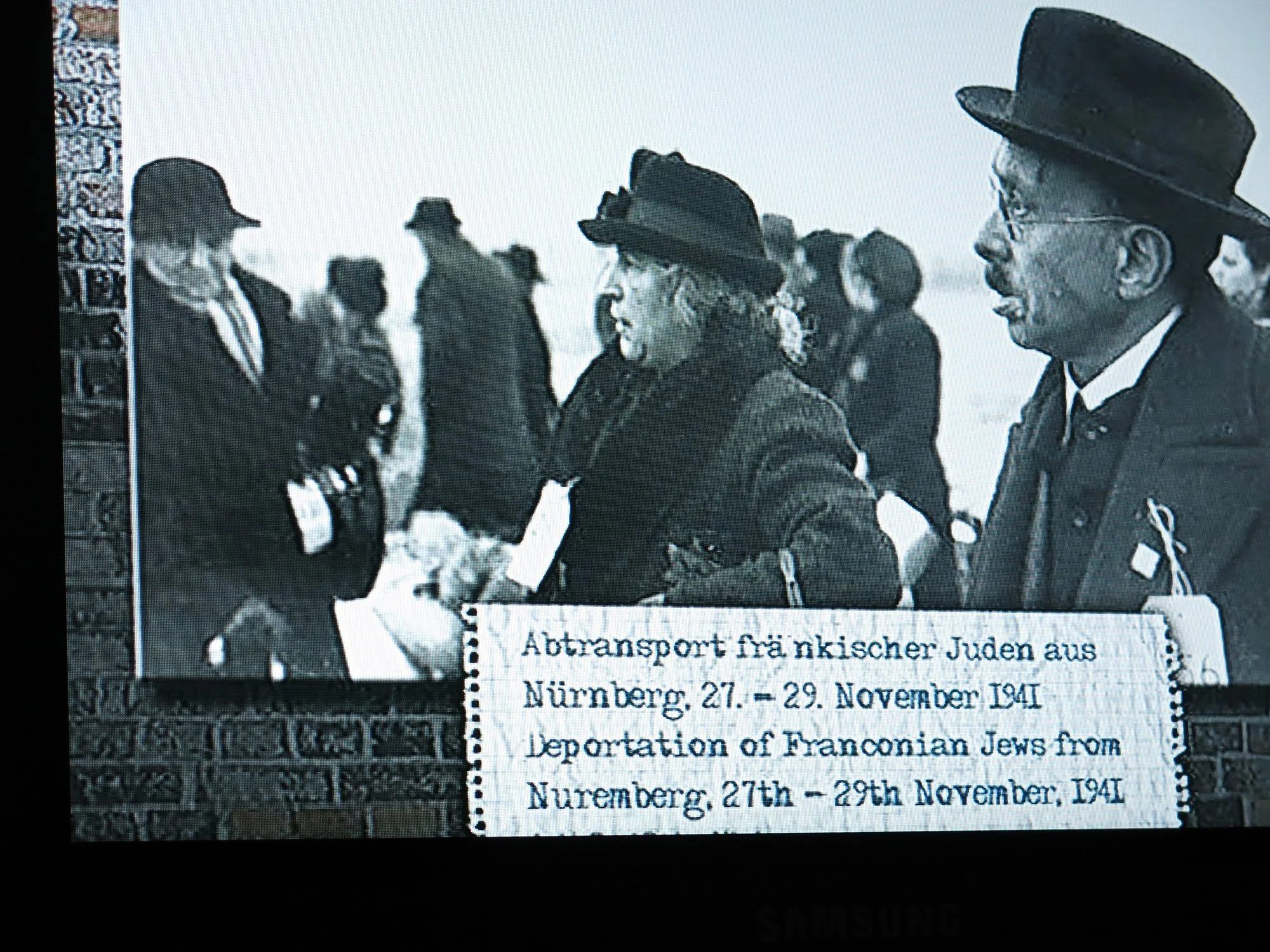

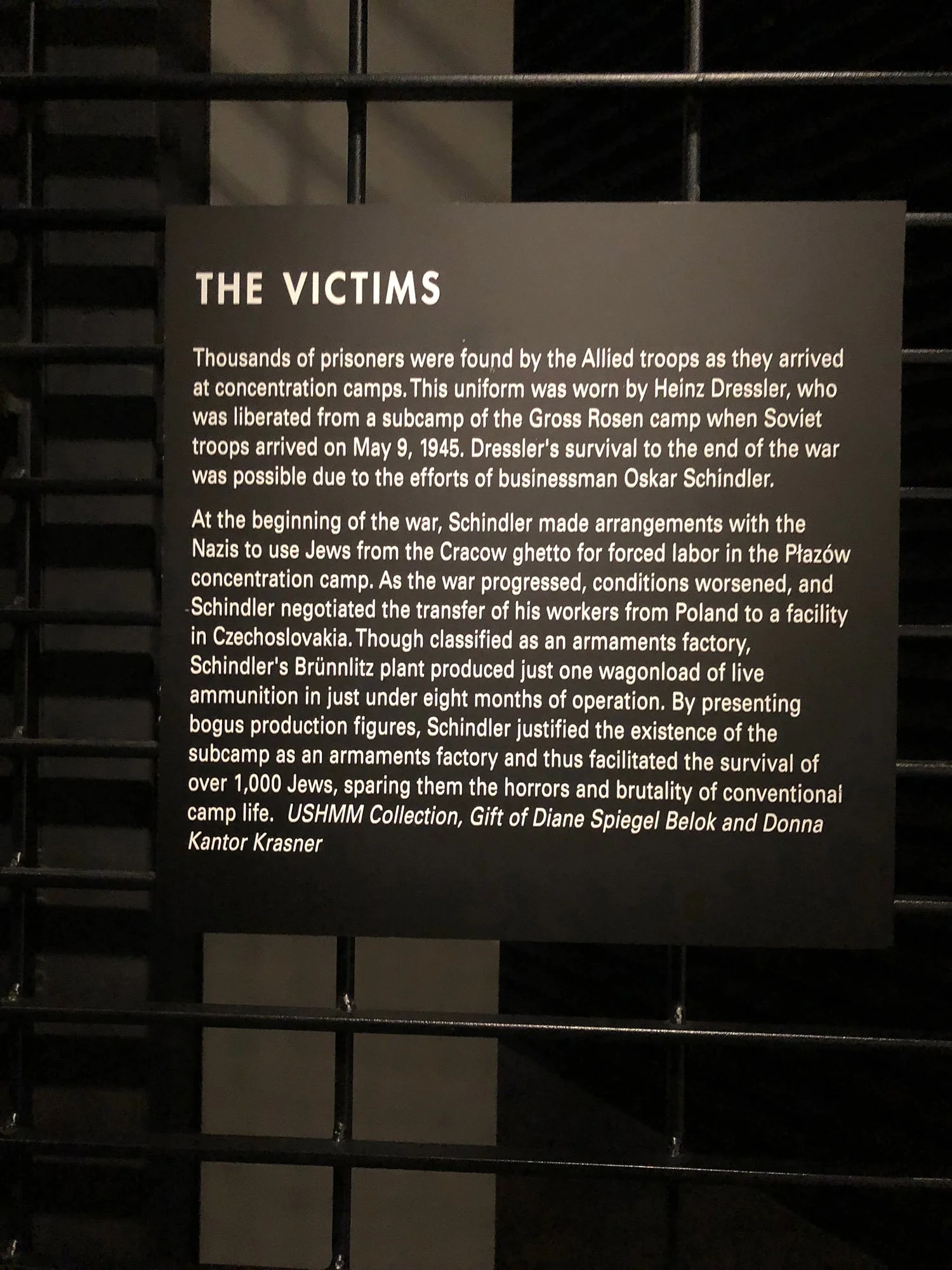

Holocaust Museum, Washington, D.C.

Ann Frank house, Amsterdam

"Schindler’s List”; One of my classmate’s last name was Schindler

Up Close and Personal

The most important thing to happen to me in Beverly Hills––the thing that I consider life-changing––I got braces on my teeth.

My mom had been unable to stop me from covering my mouth when I laughed because crowding teeth forced an upper canine to protrude. I felt terribly self-conscious of this defect.

Some miracle occurred, as far as I was concerned. The miracle happened that summer before I started school when Dr. Furstman put braces on my top teeth. Abbreviating treatment to nine months instead of four years he said it would take to give me a perfect smile without pulling a tooth, Mom made the decision for him to pull a tooth behind the one that protruded.

After pulling my tooth, Dr. Furstman sent me flowers–an arrangement like a soda fountain drink with a straw and rubber cherry. The very first time I’d ever received flowers!

I wonder if Mom knew we would leave Beverly Hills at the end of that school year. I’m glad I didn’t know what changes lie ahead.