Unraveling a Story

“If your mother hadn’t gone out there to Dallas and married your sorry daddy,” Aunt Bessie said my mother, “you could have had a happy life here. She would have married Pete Everett and he would have been your daddy.”

“He would have been somebody's daddy, but without the daddy I had, I wouldn't be here,” 10-year-old Loretta replied.

“Whatever do you mean? Of course, you would be here.”

“An unbelieved truth can hurt a man much more than a lie.”

Repeatedly, Aunt Bessie had denied a simple biological fact. My mother, however, grasped a truth Aunt Bessie failed to comprehend.

With extreme prejudice, Bessie dismissed the question. Her mind was made up. She believed what the rest of the family said about Joel Monroe Reeves––my mom’s “sorry daddy.”

Conversing among themselves, they blamed him for taking “their Prudie”––the youngest of the eight siblings––away from them.

Family Ties

I wonder if every family has in their family history an Aunt Bessie––that person who knows everything and attempts to control everyone? The manipulator. The control center. The immoveable force.

Born May 26, 1895, at age 18 my mother’s Aunt Bessie married Dewitt Brown who took her by train to live in California. The couple got as far as Dallas, where Bessie Della Smith turned back, went home to Marshall where their marriage was annulled. Afterward, the family discreetly omitted Mr. Brown from the number of husbands Aunt Bessie eventually accumulated.

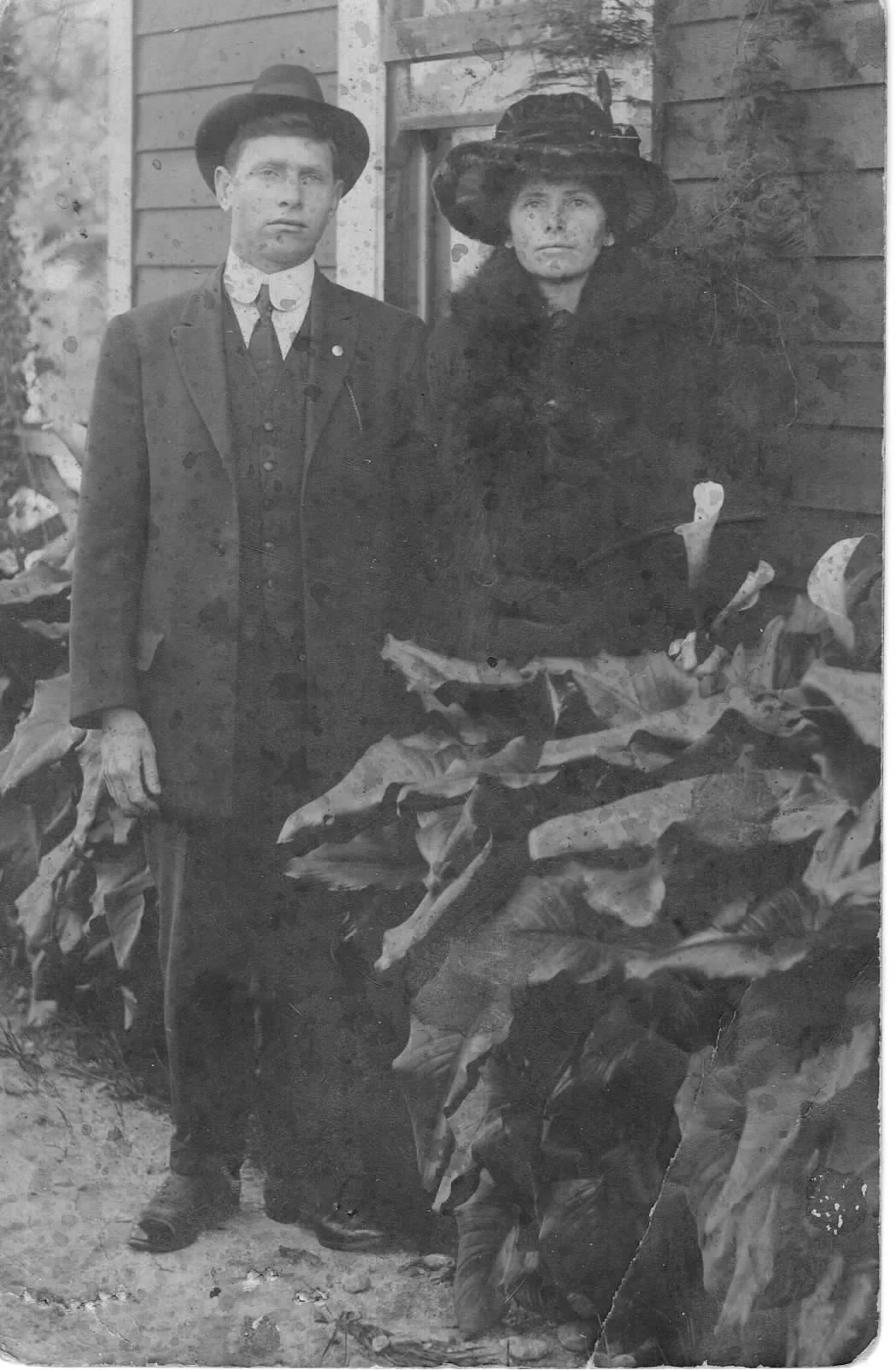

No record of this scandal might have survived but for the six-page letter the second Mrs. Dewitt Brown wrote to my great-Aunt Bessie. A gloating letter––thank you very much for breaking his heart but now he has me and we’re rich—along with the photo she enclosed. The picture captures the couple, the new Mrs. Brown wearing a fur coat and fancy hat like those worn by First Class passengers on the Titanic. Written in curly cursive, a painstaking elegy with rhyming stanzas, Mrs. Dewitt Brown titled this artifact “The Cord That Bound Three Hearts––The Will That Severed Two.”

Dewitt and Lillie Brown, 1915

Now in my possession, I refer to this faded letter as “The Ballad of Bessie Brown.”

Skip to the end, I’ve omitted pages 2–5.

A painstaking poetic effort by Lillie to punish Bessie for hurting her Dewitt

After Heartbreak

Aunt Bessie reigned over three husbands and bore no children. She married H.B. Everett soon after her marriage to Mr. Brown was annulled. Two of Bessie’s husbands died, leaving her a farm, a grocery store, and a house in town.

A ledger fails to account for the difficulty I have imagining Bessie as the object of anyone’s passion, her breasts heaving beneath any man’s head, let alone three or four––or more––different men. I knew her when she was old, wearing cotton print dresses she had made for herself where she “‘llowed [allowed] a little” on account of the “little dab of leftovers, not enough to keep,” which Aunt Bessie would rather eat than save for another meal.

Aunt Bessie in Galveston, TX cir. 1950’s

Throughout her lifetime, Aunt Bessie, the eldest of the eight children, weaved a matted web of influence on her siblings, as well as on my mother and her two sisters after their mother died. Fashioning herself as a standard of religious piety, Aunt Bessie demanded strict adherence to laws she herself did not keep. With self-righteous dogmatism, she “‘llowed a little” for her own indiscretions––as well as defended Syble’s trail of rebellion because “Syble was the baby.”

Aunt Bessie drew sharp distinctions when it came to the sins of others. Never did mote and beam apply to her.

“Of all bad men, religious bad men are the worst.”

When my mother’s mother, Aunt Bessie’s youngest sister Prudie got sick, my mother's “sorry daddy” took his 26-year-old wife to the charity hospital in Dallas––something the family insisted they would never have allowed.

The entire Smith family blamed my mother’s daddy for their sister’s death. With a ruptured appendix, peritonitis took Prudie quickly, leaving her three young girls motherless. Prudie’s death seemed to validate the family's belief that by marrying “that Reeves man,” Prudie had made a deadly mistake.

Prudie’s three sisters and four brothers all lived to crotchety old age. These sibling’s parents, Hiram Shaw Smith and Maude Vaughn Smith, outlived their youngest daughter Prudie another ten years.

As the eldest, Aunt Bessie claimed territorial jurisdiction over Prudie’s motherless girls. The family called the girls “orphans,” despite their father's existence and responsibility. From on high, Aunt Bessie determined their distribution.

Concern that sending the two older girls to Buckner's Orphan Home in Dallas would make the family look bad led to the family to keep the three girls in Marshall. Rather than concern for the older girls’ welfare, as my mother recalled her early childhood, she and her sister Joyce were then passed “pillar-to-post.”

Seven years old, my mother lived for a while, off and on, with Aunt Bessie and at other times with her grandparents, Ma and Papa. Loretta adored her grandfather––Papa, “a hard-shell Baptist.” Ma, who had raised her eight children, could only manage one of Prudie’s girls, and so Ma and Papa kept Joyce.

My mother's younger sister, Joyce, age five when their mother died, lived with Ma and Papa until Ma died. “When Ma died, I remember telling my cat, I will never love anyone else as they all die.” After Ma died, Aunt Roxie and Uncle Jake, newlyweds, moved in at Papa’s farm to take care of Papa and Joyce.

“Aunt Roxie resented it,” Joyce said. “She was never good to me. My hands shook so bad I could hardly hold a plate.” One time, “Aunt Roxie hung my cat by its tail on the clothesline.” Joyce ended up being sent to a convent in Phoenix when she was fifteen, which she said was the best thing that could have happened for her.

Aunt Bessie and her sisters fought among themselves for custody of the baby Syble, age sixteen-months when Prudie died.

Both my mother and Joyce (my “Auntie”) grieved and commiserated how their lives changed after their mother was taken.

Where to turn and Who to trust?

Oh, the lamentable hardships and sorrows in my mom’s childhood that shaded her future, extending with twisted branches to tangle and overshadow parts of my own.

Little wonder that my mother didn’t know where to turn or who to trust.

In order to appreciate what I might learn from the backseat of my mom’s life, I have needed to unravel her story.